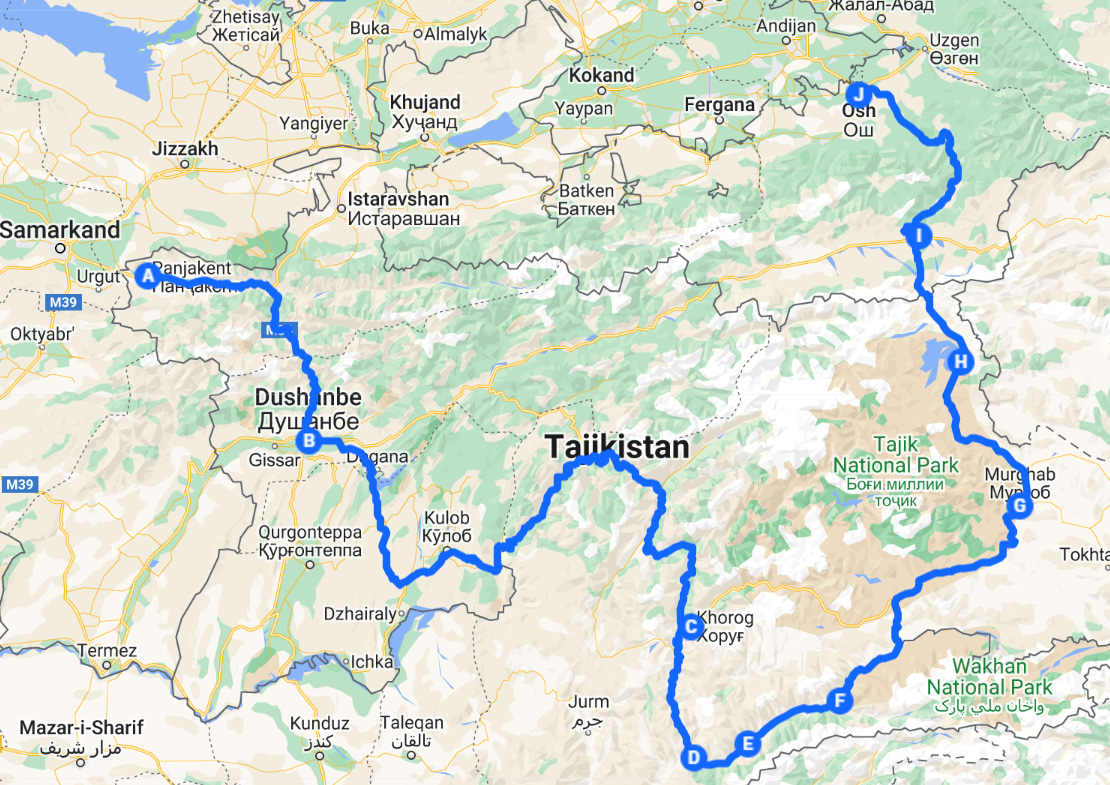

Pamir Highway

Welcome to the Pamir!

The first drive was the worst. For twenty hours we sat crammed into a Toyota Landcruiser, every seat filled and the luggage secured to the roof, knees pressed against seatbacks, head crouched, shoulders cramped. Quite the welcome, after all.

The drive first brought us south through Khatlon Province, Tajikistan’s poorest whose agrarian locals subsist on $200 per year, and after hours along its cultivated plains we came to our first exciting landmark: the border with Afghanistan.

We had arrived at the Panj River, the dividing line between Afghanistan and Tajikistan, which we would cling to for 700 kilometers. At times the river was no more than twenty meters across and we could look in the faces of Afghan villagers on its far bank. While a paved road runs on this side, only a dirt path connected the opposing villages. Two sides of a river, but worlds apart.

Taliban flags flew above villages and while we never spotted a single woman - surely they were holed up inside - we thought of the young girls who were barred from attending school by their new government.

We stopped once to pick up some goods and share in a family meal before hopping back in the car for a dozen more hours.

We had teamed back up with Roger from the Fann trek and also found Belgian Robison in our hostel, and together convinced one another to take to the road tour-less. With much unknown and zero public transport in the region, our plan was to unite when the need to split taxis arose and to share info along the way.

Day turned to night and it wasn’t until after 1 AM that we arrived in Khorog. After a feeble thanks to our driver - who had driven the 20 hours with no sleep - we crashed into our room.

Khorog

The coming days were spent enjoying Khorog, the capital of the autonomous region of Gorno-Badakhshan (GBAO), which 25 years ago waged a civil war against Dushanbe and the west. As the unfortunate losers, the region and its Pamiri people have been the recipient of little aid from the government.

Thankfully, where federal aid has lacked, the Aga Khan Foundation has stepped in. Pamiris are Ismaili, a progressive branch of Islam which views the Aga Khan as their spiritual leader. In response, the Aga Khan Foundation sends aid by the truckload, and against all odds Pamiris have some of the highest rates of education, female workforce involvement, food security, and access to medical services in the country. It was a joy to see firsthand the difference that effective philanthropy can make.

A couple Khorog days were spent recovering from the drive while exploring the fascinating little town on the edge of the unknown and familiarizing ourselves with its proud Pamiri heritage.

Despite lying on opposite ends of the Earth, Khorog reminded me in spirit of Yurimaguas, a town found at the edge of the Peruvian Amazon. The road ends in Yurimaguas, with journeys deeper into the jungle requiring a boat, and thus evokes equal parts adventure and opportunity. In the same way, while on its face Khorog was no more than a dusty mountain town, it felt magical and full of potential. It was our gateway into the heart of the Pamir, and it’s a place I’ll always cherish.

Jizeu

Mack had gotten sick and needed some extra rest in Khorog, so together with Roger and Robison I tacked on a side trek in the nearby Bartang Valley. The others took a shared taxi to the trailhead while I tried my luck at hitchhiking and was exceedingly proud to beat them there.

As usual, hitching proved a wonderful way to interact with locals, and on the way to the Bartang Valley I shared a conversation with a gentleman before being invited for lunch at the driver’s home. The people here in the valley speak Bartangi, a micro-language with only about 2,000 speakers, but we were able to converse using my terrible Russian.

Arriving before the others, I hiked solo and thoroughly enjoyed the solitude that fifteen kilometers through the Bartang and Jizeu Valleys brought me.

I arrived at Jizeu for dinner, where I was soon reunited with Roger and Robison.

Together we continued a few kilometers beyond the village for the best views of the snowy mountains at the end of the valley.

Returning to Jizeu, we shared a dinner with our hosts, the daughter of whom could speak some English and gave us fascinating insight into what life in a village of seven homes looks like. For half the year, snow makes the hike out of the valley impossible. Cut off entirely from the outside world, completely self-reliant, fully at the whims of the weather… a life like this has not been lived in the US for a very long time, if ever. We closed out the night by claiming a spot atop the raised platform of packed earth that’s a feature in all Pamiri homes and unrolling our sleeping bags to the symphony of ribbiting frogs and rushing river.

I rushed out the next morning, leaving Rob and Roger behind and wanting not only to return to Khorog, but to continue to our next stop. A lucky hitch brought me back to Khorog in record time only for Mack and I to spend four grueling hours at town’s edge failing to find a ride onwards. We were stuck in the city for another night.

The challenges here foreshadowed the difficulty to come as we entered the most sparsely populated parts of the country.

Ishkashim

The next morning, we headed to the unofficial bus station, where after a few hours we’d filled a van going to Ishkashim, our first stop in the Wakhan Corridor.

The Wakhan Corridor is an offshoot of the official Pamir Highway which instead leads travelers along the Afghan border and through the Wakhan Valley that the two nations share. The mountain scenery is dramatic and the village lifestyle fascinating, but being off the main way means little traffic, and it would pose our greatest challenge to independent travel.

Once arriving in Ishkashim our luck took a turn for the better, and we hitched a few rides on the way to Darshai, where we spent the night.

Along the way we explored the Qahqaha Fortress, ruins from the once-great Kushan Empire which ruled this valley in the 2nd century BC during the earliest days of the Silk Road. The fortress stood proud on a rock outcrop overlooking the Panj for nearly a thousand years before the Arab conquest swept through the region, destroying everything in its path.

Our final ride of the day was the most memorable, as we were stranded between villages with the sun creeping towards the horizon. It can be hours between cars on these roads, so, not wanting to sleep under the stars, when we saw a truck eclipse the far hill, we waved our arms and jumped like crazy people such that they had no choice but to stop. Inside was a band of soldiers who gladly took us in.

With no space, I sat on the back of the truck alongside the youngest cadet while Mack had a seat of honor inside crammed between three oversized soldiers. After a 20-minute ride, we arrived in Darshai.

Darshai

Darshai was a village of no more than a dozen houses, and we stayed at the homestay of a man who we’d shared a car with that morning.

A village stroll brought us upon a friendly troupe of local guys, who after some shared jokes directed us up a mountainside for the town’s main attraction: Darshai Fort.

Within Darshai also lies the most fascinating of many shrines in this section of the Pamir. A plastered wall and horn-guarded entryway surrounds a central table piled high with revered ibex horns. While the locals are Ismaili Muslims, it’s no surprise that animist traditions live on here; when being surrounded by soaring mountains and having your livelihood depend on the temperament of the river, it’s easy to ascribe divinity to the land.

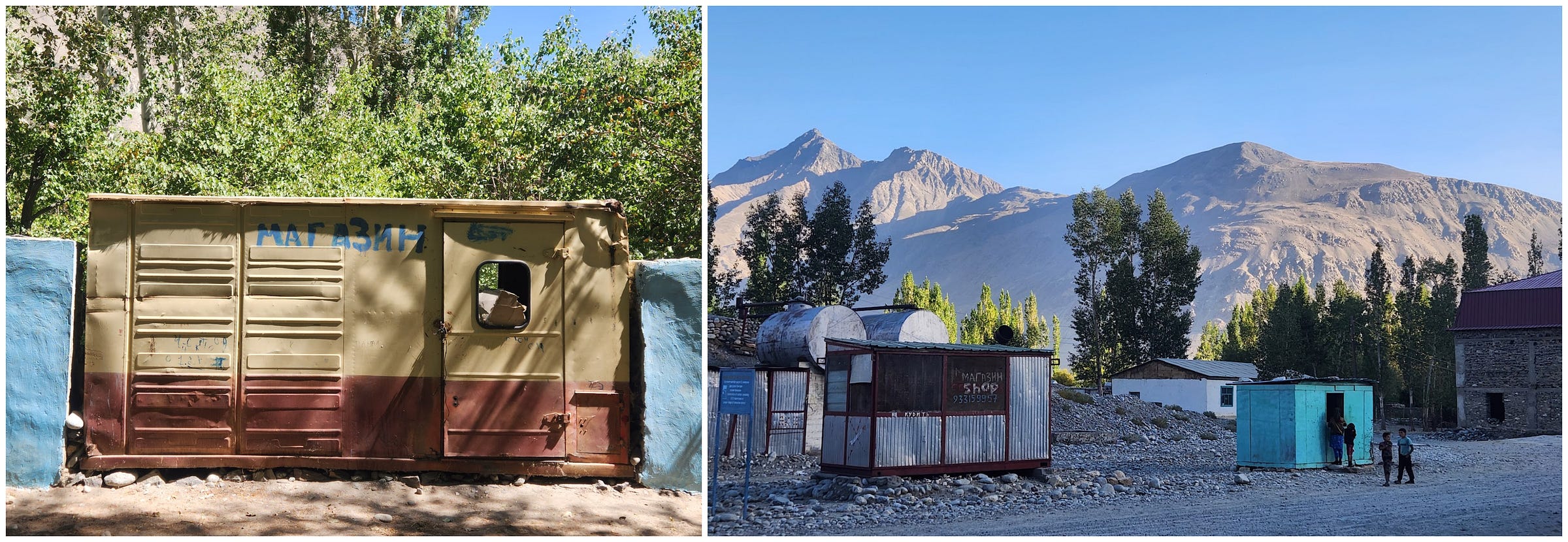

The next morning we were back roadside and getting into our groove. Patience was necessary hitching here. No more than a couple cars passed each hour, and they were always full, meaning our rides were limited only to those willing to squeeze us in. When we did find a car, it was only to the next village, often little more than 10 kilometers down the road. But we expected this, and with good spirits we enjoyed the long waits, always accompanied by spectacular mountain views and - in the case of leaving Darshai - an age-old shrine.

Yamchun

We made a midday stop in Yamchun, where we were promptly spotted by and invited into a local’s home for lunch before visiting the town’s 3rd century BC fort.

Hiking slowly to the fort, getting lost in the maze of goat paths and saved by farmers, sharing impromptu meals with new friends… this is what stood out to us on the Pamir, especially in this Wakhan section. The locals were spectacular and traversing the road independently let us savor every spontaneous encounter. It wasn’t easy, but looking back, we both have nothing but happy memories from these long days.

From Yamchun, a few more primarily roadside hours brought us to Vrang.

Vrang

After a quiet night in Vrang, we started the morning with a short hike to Vrang Stupa, the remains of an ancient shrine that serves as the only evidence that Buddhism had a brief hold here before the introduction of Islam.

Back in town, we waited for half a day to find a car going our way, giving us plenty of time to observe the slow pace of village life.

By evening we’d made it the 30 kilometers to Langar, our last stop on the Wakhan Corridor.

Langar

From Langar, the road pulls away from the Panj River and climbs up and up endlessly to what’s known as the “Roof of the World”, the Pamir Plateau.

It’s over 100 kilometers between Langar and connection with the true Pamir Highway, and with precisely no habitation between these points, we were told that no cars would be going. Unperturbed, we attempted hitching, and thus tallied up our longest wait of all time: two full days. Well, about 40 hours to be exact.

That said, while we technically waited forty hours, if we didn’t catch a ride by noon, we were done for the day as no cars begin the long haul in the afternoon. Thus, half-days were spent exploring the village and its surroundings, chatting with tour groups coming in for the night, and devising a Plan B.

On our third morning in Langar we decided it was time to pay for a cab. Plus, by now we’d built a crew: Roger and Rob had caught up, and we also teamed up with Kenta, a Japanese guy also braving the road solo. The five of us split the price and were off, covering the 120 barren kilometers to Alichur, the first town back on the highway.

For five hours the road brought us endlessly up, lifting us from the Wakhan Valley and carrying us to a new world: the high Pamir.

Shortly before arrival in Alichur, we arrived atop the Pamir Plateau to a tremendously different environment. Gone was the Panj River and its fertile floodplains, gone were the fields of wheat and the apricot groves. In their place sat desolation. We were now at 4,000 meters elevation - over 13,000 feet.

That said, while the terrain evoked death, we were thrilled to see signs of life: a distant 18-wheeler was bumping along the pocketed road towards us. Our hitchhiking odds would soon change and a new phase of the Pamir Highway was about to begin!